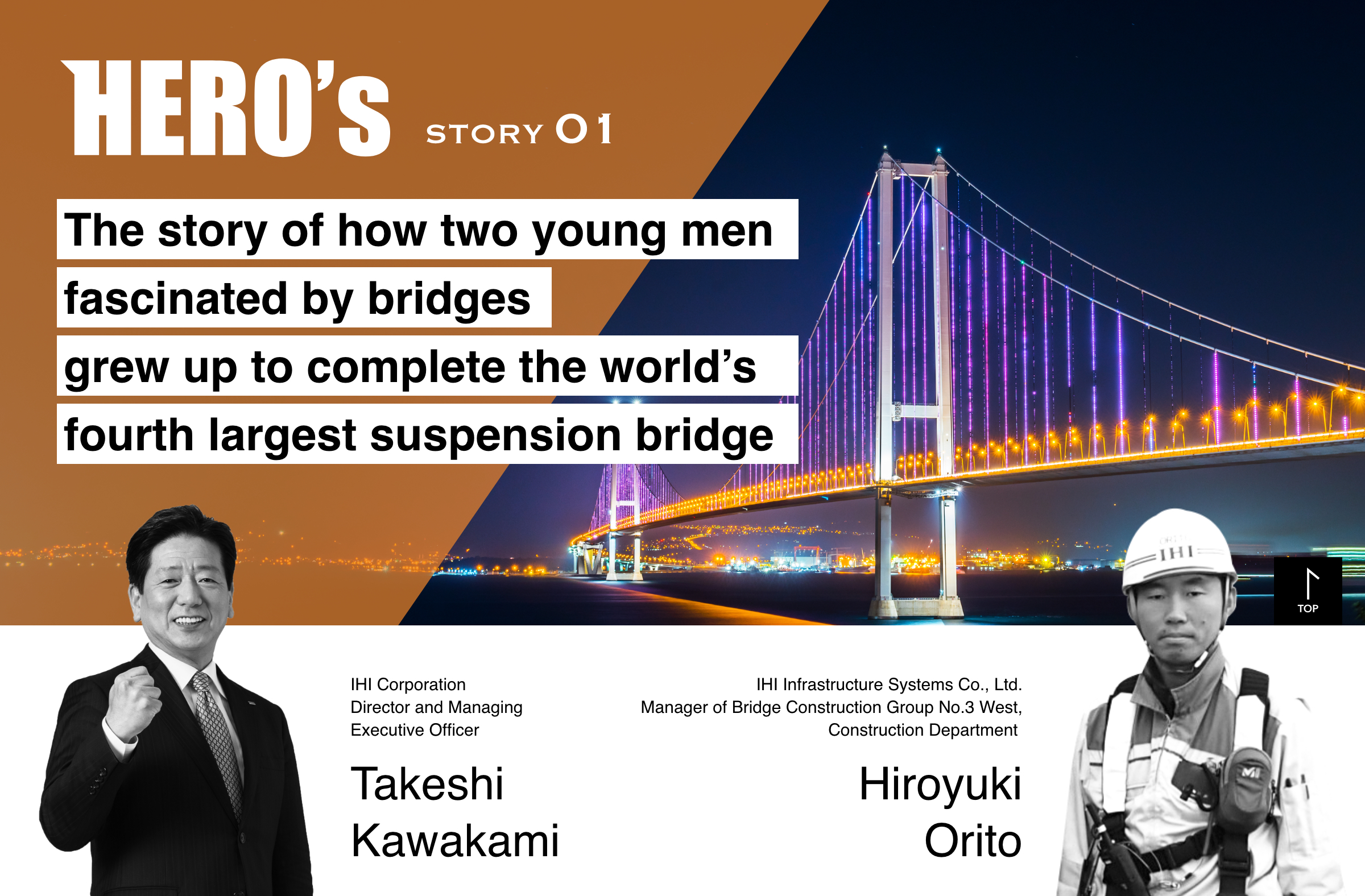

Istanbul, the largest city in Turkey, has a population of roughly 14.8 million people. The area, which is divided into two sections by the Bosphorus Strait, had suffered from chronic traffic congestion because there were only three road bridges, one road tunnel, and one railway line.

As a part of the infrastructure policy aimed at rectifying this situation, Turkey implemented a project to construct a highway connecting Istanbul and Turkey’s third largest city, Izmir. This marked Turkey’s first BOT road project that includes a bridge, and within this larger project, IHI Infrastructure Systems Co., Ltd. served as EPC*1 contractor for the Osman Gazi Bridge (Izmit Bay Bridge) Project, which greatly contributed to shortening travel times.

The following focuses on the story of two Japanese men who had dreamed of large-scale bridge construction since they were students and who finally achieved this dream in a distant and foreign country.

*1 EPC: Abbreviation of Engineering, Procurement and Construction. Refers to undertaking the entire process of design, procurement and construction.

The dream held by two junior high school students

The dream held by two junior high school students

The trip used to take roughly an hour by ferry and about 1.5 hours via the land route around the bay, but construction of the Osman Gazi Bridge shortened the travel time to approximately six minutes. This, along with its economic effects, prompted local media sources to praise the bridge as “the pride of the Turkish people.” The heroes of this story are Mr. Takeshi Kawakami, who served as project manager at the time and who single-handedly bore responsibility for the project, and Mr. Hiroyuki Orito, who served as superstructure site manager at the time and who took charge of construction management at the forefront of the site.

“I first became interested in bridges during my second year of junior high school. I became interested in a career building bridges after seeing Kanmon Bridge while on a school trip and Onaruto Bridge, which was still under construction at the time, while on a family trip.” (Mr. Kawakami)

Mr. Kawakami studied civil engineering in university and graduate school, and he also majored in bridges. When he was conducting wind tunnel experiments on large bridge structures, he decided that he wanted to work at IHI Corporation, which was responsible for examining the wind stability of the Akashi Kaikyo Bridge at the time. Even during his recruitment interview, he passionately expressed his desire to participate in that project and was offered a position. After joining the company, he served as the general manager of the Overseas Project Department and Bridge and Road Engineering Department as a bridge construction specialist, and was involved in the construction of the Meiko-Chuo Bridge (Nagoya City, Aichi Prefecture), one of the longest steel cable-stayed bridges in Japan, from the design phase through to completion of installation. Ever since the founding of IHI Infrastructure Systems Co., Ltd., he has served in a variety of positions in the company, including general manager of the Project Department in the Engineering Division.

Mr. Orito, the other hero, also first took an interest in bridge-building in junior high school. It all started when he passed over the Seto Ohashi Bridge and Onaruto Bridge while on a family trip.

“I think my father was trying to show me the Naruto whirlpools, but my attention was captivated by the grandeur and beauty of the bridge itself. Ever since then, I have loved suspension bridges, and I realized that I wanted to make a career out of building magnificent-looking structures like this in the future.” (Mr. Orito)

Although he majored in mechanical engineering in university, when looking for employment, he focused on bridge-related companies. Just like Mr. Kawakami, he joined IHI immediately after graduation. Ever since then, he has been involved in bridge construction, and after working for around five years in the Marine Structure Manufacturing Division, he transferred to IHI Infrastructure Systems Co., Ltd. in order to work on bridges again.

These two men teamed up to handle this project. The story goes back to 2011 when Mr. Kawakami was appointed as project manager.

“Although we had been involved in a number of overseas projects in the past, this was the first time that our company was to handle construction of such a large-scale structure all on its own. To be honest, I was considerably worried, but I undertook the project because I realized that I might never get another chance like this again.” (Mr. Kawakami)

Around that time, Mr. Orito was working on site at a bridge construction project within Japan. One night, he received an international phone call from Mr. Kawakami, who was already in Turkey.

“He asked me if I wanted to go to Turkey. However, I was still inexperienced as a domestic construction engineer. If I went, I would be joining the project in Turkey after it had already started, so at first, I declined. However, thankfully, he scolded me for my hesitant stance and demanded that I rethink my answer. Ha-ha.” (Mr. Orito)

“I knew how passionate he was about suspension bridges, and I saw how well he handled foreign clients when he was in charge of marine structures, so I wanted to entrust the project to him. I convinced him by saying, ‘If you let this opportunity slip by, there’s no telling when the next one will come.’” (Mr. Kawakami)

Although he initially resisted, Mr. Orito eventually decided to take on the challenge after being repeatedly and enthusiastically persuaded. With this, a major project destined to become a lauded episode of the company’s history began in earnest.

Pressure felt at the top

Pressure felt at the top

This was a BOT-contract*2 project to comprehensively design, construct and operate roads and bridges using massive funds independently procured by five Turkish and Italian construction companies. Our company participated as an EPC contractor in charge of designing and constructing the Osman Gazi Bridge (a suspension bridge). It all started from a vacant plot of land from which only a hill on the other side of the strait could be seen. Mr. Kawakami, who was in charge of the project, was under a considerable amount of pressure.

“Our company had conducted several construction projects in which we handled all aspects of the process. However, we had to build not only the upper portion of the bridge but also the submerged foundation. And it was going to be the world’s fourth largest bridge, so naturally, we had never experienced such a large-scale construction project. I was certainly worried about whether or not I could successfully manage the project.” (Mr. Kawakami)

*2 BOT: Abbreviation of Build, Operate, Transfer. A project format in which a private business operator constructs, maintains, manages and operates a bridge or other public facility, and after completion of the project, transfers ownership of the facility to the national or local government.

In addition to the massive scale of the project, the company was also assigned the short period of only 3.5 years to complete construction. At less than half of the roughly ten years required to complete the Akashi Kaikyo Bridge, this was an extremely tight schedule. Shortening the work schedule naturally increases the costs involved, and if the deadline is not met, the company will be subjected to a penalty of roughly 200 million yen for each day of delay. While following a schedule that did not permit even a day or two of hesitation, Mr. Kawakami was busy each day checking the overall progress and making important decisions.

Also, when conducting overseas projects, a consultant manager referred to as “the Engineer” acts as a liaison with the construction site, and the presence of this engineer put further stress on Mr. Kawakami.

“The initial Engineer came at me pretty hard with questions and demands like, ‘What sorts of projects have you worked on so far?’ ‘How much overseas experience do you have?’ Show me your project execution plan in detail and in writing.’ And each time I answered, he treated me like an amateur. He would also sometimes lecture me and further insult me saying, ‘You’re English in unintelligible.’ Even though we were pressed for time, we couldn’t get approval, and for a while, we couldn’t progress beyond the design stage.” (Mr. Kawakami)

However, the initial Engineer was transferred, which resolved the situation. The project finally made a turn for the better with the arrival of a new Engineer with extensive on-site experience.

“I learned a lot from the new Engineer. He viewed things on a large scale and made decisions very quickly. When I was worried about costs in terms of differences of one or two million yen, he said, ‘You’re worried about tiny peanuts.’ Of course, I was doubtful at the end, though, when he said that even cost differences in the 100-million-yen range are peanuts. Ha-ha. I felt the difference in scale between people born in Japan and those born in the Ottoman Empire.” (Mr. Kawakami)

Dilemma faced at the forefront of construction

Dilemma faced at the forefront of construction

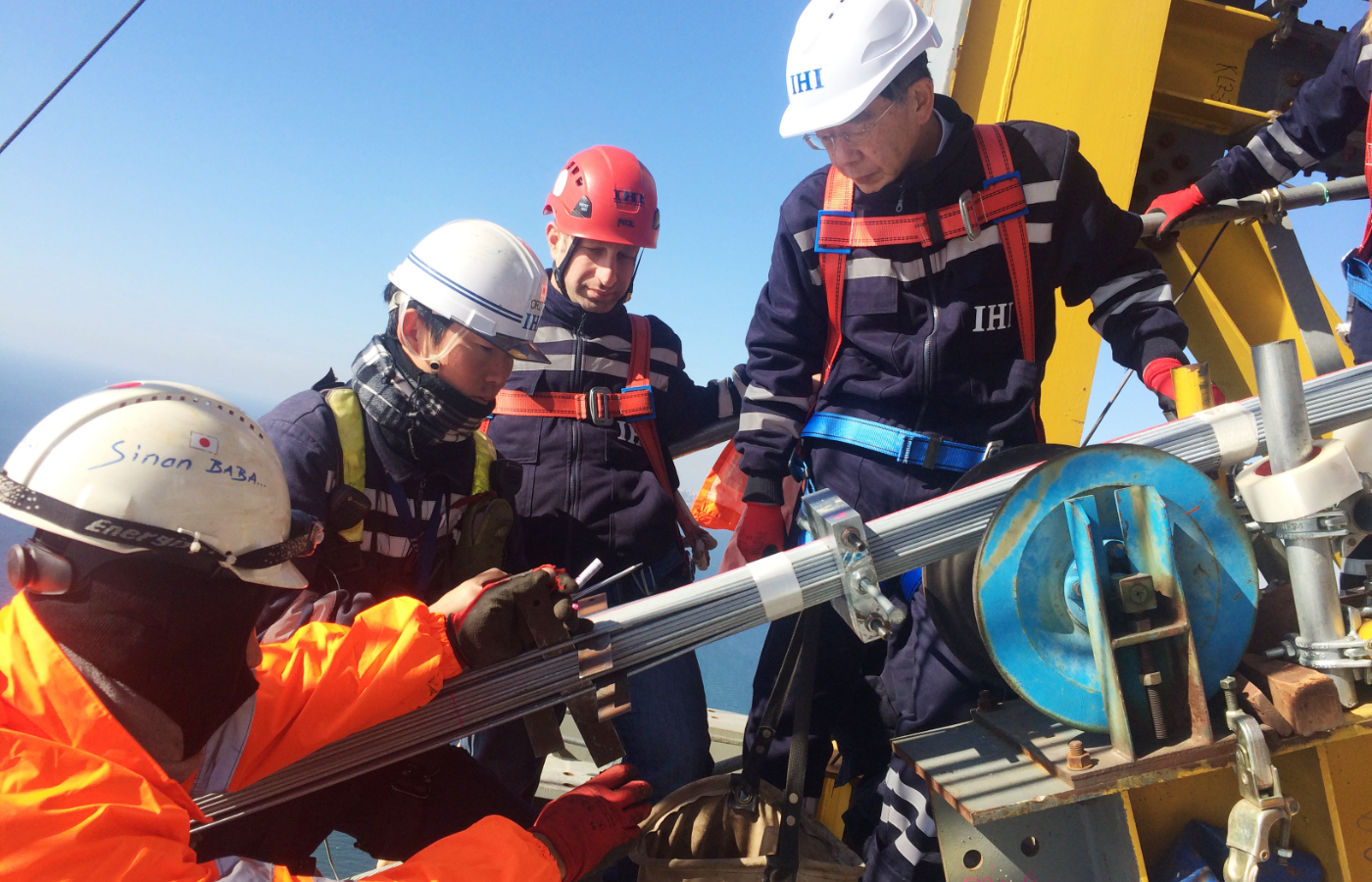

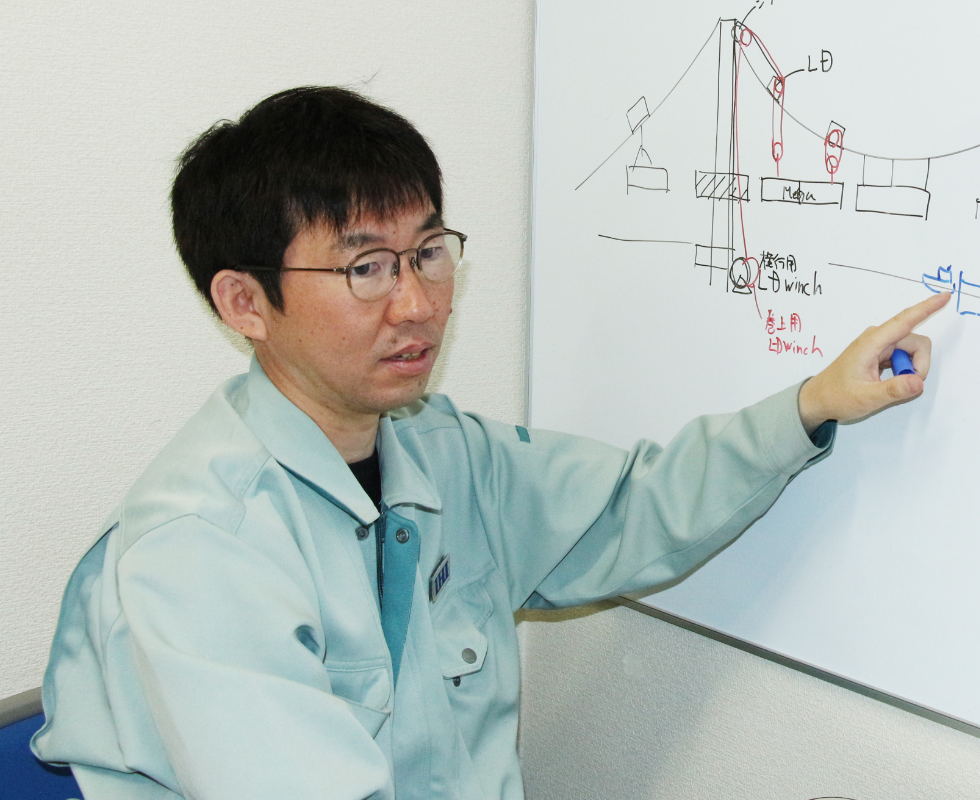

Around the same time, Mr. Orito was managing on-site construction as the foreman of the southern construction area for the Osman Gazi Bridge. Each group was composed of around five local Turkish staff members assigned to one Japanese bridge scaffolding worker participating as a supervisor, and roughly ten such groups were working in each construction area. Mr. Orito managed these as the on-site leader, and he handled everything from process management through to labor management.

“My role was to conduct so-called ‘on-site supervision.’ However, compared to the administrative duties I had performed in Japan, my role on this project was more focused on personnel management than on the construction work. The Turkish staff members made many demands for things like higher wages, better lunches, and so on, which took time away from the work that I should have been doing. To be honest, it was a dilemma.” (Mr. Orito)

It was a different workstyle and a different culture. This project was also being handled as a Turkish national project, and it even included events that would be attended by the president and prime minister. On top of the extremely tight construction schedule, the country specified a diverse and detailed schedule of public openings.

While at the mercy of distractions that do not exist at Japanese construction sites, Mr. Orito naturally also needed to manage the construction process, including issuing work assignments to each group, ensuring the safety of the workers, and ensuring quality, among other things. On top of that, this was the first time that Mr. Orito himself had ever managed the construction of a suspension bridge. He faced a lot of unseen anxiety, so he was under a different kind of pressure than Mr. Kawakami.

“Even under these conditions, Mr. Kawakami wouldn’t compromise. To be honest, there were times when I thought, ‘What? How can you demand so much!?’ But Mr. Kawakami had a deep understanding of on-site conditions without me needing to point them out, and he protected us by bearing the brunt of it himself. Knowing that this situation underpinned his orders motivated me and the other senior members and supervisors to get to work.” (Mr. Orito)

Supportive passion and an enlightening comment

Supportive passion and an enlightening comment

Mr. Kawakami and Mr. Orito faced a broad range of difficulties, but they were supported by the bridge scaffolding workers participating from Japan as supervisors. The presence of specialists who were as proud and passionate about bridge-building as our two heroes enabled the tightly-scheduled project to move forward steadily.

“They all truly loved bridge-building, and they worked very hard. Because it’s not every day that they get the opportunity to build the fourth longest bridge in the world. They did their best while reminding each other that ‘accomplishing this project is worthy of an Olympic gold medal’ for encouragement.” (Mr. Kawakami)

“Despite our tight schedule, they always worked with a positive attitude and without complaint. Being able to work together toward a common goal with people who felt the same way helped us remain positive as well.” (Mr. Orito)

Their passion also gradually rubbed off on the local Turkish staff members. Although, at first, they had been working as though the project were an extension of a part-time job, they did their best to understand their supervisors’ instructions, which were mixed with Japanese words and phrases, and to carry out their tasks. As their mutual trust deepened, they also continued to steadily improve their skills.

“A Turkish staff member once told me, ‘Leaders should remain smiling and forward-looking at all times. They must never look down.’ I still appreciate that comment.” (Mr. Kawakami)

The project faced numerous crises along the way due to planning errors and unexpected accidents. At times like that, the project overcame its difficulties with Mr. Kawakami’s conviction to “never give up” as its slogan. The suspension bridge, with a total span of 2,682 meters, was completed in the short period of just 48 months from the time of commencement, including the initial six-month preparatory period. To this day, this remains the world record for the fastest construction of a large suspension bridge.

A bridge of hope for the future

A bridge of hope for the future

Throughout this project, Mr. Kawakami remained conscious of the need to train and develop younger workers.

“In recent years, even in our industry, there are many young people who do not want to work overseas. However, it is necessary to increase the number of experienced personnel in preparation for the next overseas project. I believe that the experience of working on-site overseas while young will change people’s minds.” (Mr. Kawakami)

Mr. Kawakami, who undertook this project in his late 40s, says that it drastically changed his own outlook on life. Looking ahead at the development of not only our company but the civil engineering industry as a whole, he calls on younger workers to build up more experience overseas.

In fact, in this project, the company accepted not only young in-house engineers but also student interns both locally in Turkey and from Japan. This was to convey the appeal of bridge construction and overseas construction projects to the young people responsible for the future of the construction industry.

One of these young workers is a Turkish engineer that Mr. Kawakami had interviewed and hired. He became interested in bridge-building when he witnessed the construction of the Second Bosphorus Bridge in Istanbul when he was a child, and he eventually joined the same company that built it. And on this project, he served as Mr. Kawakami’s right-hand man all the way from the time the order was received through to completion of the project. He realized his childhood dream in his home country.

“He negotiated with local clients and removed a lot of friction for us. Leveraging his experience on this project, he is now involved in building a suspension bridge over the Danube River in Romania.” (Mr. Kawakami) “He and some of the other young Turks who worked as staff members on this project are now serving as supervisors for a similar suspension bridge being constructed in Romania. It was a tough construction project, but if it conveyed the joy of bridge-building, then I’m glad.” (Mr. Orito)

Respective views on their accomplished dreams

Respective views on their accomplished dreams

When asked about their impressions now that the project is over, our two heroes gave contrasting answers.

“It was probably the last bridge-related project that I will be involved in on site. I served as project manager for an overseas suspension bridge, which is what I had most wanted to do. And although there were hardships and difficulties, all I can say is that being involved in every step from design to construction made me feel truly thankful that I’m a bridge-builder.” (Mr. Kawakami)

Mr. Kawakami expressed his satisfaction at achieving the big dream he has carried ever since he was a student. Mr. Orito, on the other hand, expressed his regrets.

“Of course, I feel a sense of accomplishment, but my desire to do things differently next time is stronger. Even now, I sometimes recall times when I feel I should have done things somewhat differently.” (Mr. Orito)

Finally, both men spoke about the appeal of bridge-building.

“The appeal of bridges is that they are the civil structure that can be built to extend the farthest. People often used the word ‘Bridge,’ but providing access to a far-off shore that was previously inaccessible is a way of making the dreams of the many people who live near there come true. Also, I like that they are visible, unlike tunnels. I believe that suspension bridges are a form of art. In particular, I feel that the Osman Gazi Bridge is exceptionally well-proportioned.” (Mr. Kawakami) “Simply put, it’s about making ‘connections.’ For example, building a bridge can provide an elderly woman in a rural area with direct access to a location that she used to have take the long way around to reach. Connecting locations where originally nothing existed completely alters people’s lifestyles and the scenery, and people will be grateful to you for it. I feel that it is a very rewarding career.” (Mr. Orito)

Following the project, Mr. Kawakami was appointed as president of IHI Infrastructure Systems Co., Ltd. He is currently involved in managing the head office as a Managing Executive Officer at IHI Corporation. Mr. Orito handles administrative work on-site at construction projects in Japan as a construction section manager. At the same time, he also makes every effort to train and develop the younger workers responsible for the future of the civil engineering and bridge industries by drawing on his experiences in Turkey to give advice on the suspension bridge currently under construction in Romania, among other things.

-

-

Period : From January 2013 to June 2016

Procuring Entity : NOMAYG JV (a construction supervision corporation by companies participating B in BOT project)

Applicant : IHI Infrastructure Systems Co., Ltd.Relevant Companies

Design : IHI Infrastructure Systems Co., Ltd.

Construction : IHI Infrastructure Systems Co., Ltd.