History

Japan is a country comprised of four major islands and numerous minor islands. It is configured as a crescent shape

and situated to the east of the Asian continent in the Northwestern Pacific Ocean. Of its 378,000 square km of land,

about 70% is comprised of mountainous terrain. It is inhabited by more than 120 million people.

It is a country that has achieved harmony between its traditional culture from ancient eras and its modern society

with advanced technology. Yet, Japan’s fascinating natural environment is one that changes from season to season.

The history of land transport in Japan began over two thousand years ago and can roughly be categorized into the

following four eras: 1) Age of People and Nature (ancient times until the Meiji Restoration in 1867), 2) Age of Modernization

(from the Meiji Restoration until the 1950s), 3) Age of High Efficiency Networks (from the 1950s to the

present day), and 4) Age of Optimal Maintenance and Management for Maximum Utilization of Existing Roads.

l. Age of People and Nature (Ancient times until the Meiji Restoration in 1867)

l) The Ancient Foundations of Modern Japan

The oldest written record of roads in Japan appeared in a

Chinese history book from the 3rd Century called Gishiwajinden.

At that point in time, Japan was in the process of

unifying the country under the Yamato Dynasty. People

travelled on foot or horseback for hundreds of years until the

Meiji Restoration, when Japan opened its doors to the

modern nations of the West late in the 19th century, which

resulted in modern conveniences becoming available and

then prominent in Japan.

Unlike in China and the European countries, horse-drawn

carriages never fully evolved in Japan. The historical lack of

use of horse-drawn carriages could be due, in part, to the

country’s terrain which is mostly mountainous and

criss-crossed by numerous creeks and inlets.

After the Reformation of the Taika Era (645 C.E.), an elaborate

central government system, characterized by emerging

administrative and judicial institutions, was established. A

new road network was developed at this time that

connected Honshu (the largest island) to Shikoku (the

smallest of the four main islands) and then continued all the

way down to Kyushu (the southernmost and third largest

island).

This nationwide public road network was called “Seven

Roads”, and was composed of Tokaido, Tosando, Hokurikudo,

San-indo, San-yodo, Nankaido, and Saikaido (‘-do’ in

Japanese means ‘road’). After bitter struggles with the rough

terrain of the country, the Seven Roads were completed and

in later years were used as the prototype for highways and

roads. Almost all of the Seven Roads routes were used as

arterial railways during the Meiji Era (~1868 C.E.) and then

expressways that opened after 1964. In short, ever since

the Seven Roads were first established during this age, they

have continued to serve as the backbone for transport routes

in Japan.

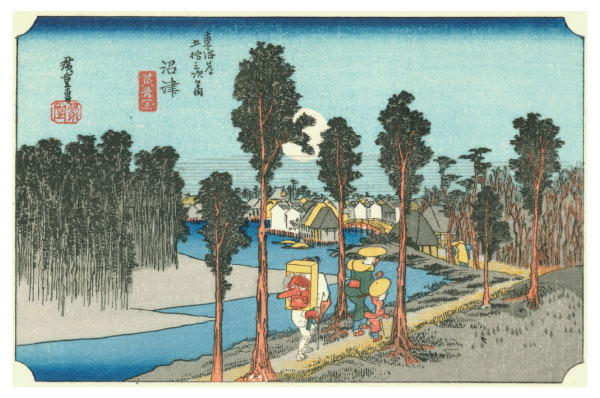

Numazu-juku as depicted by Hiroshige

Source: National Diet Library

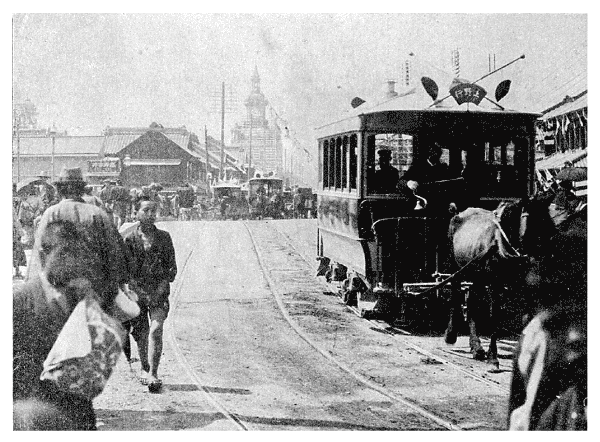

Nihombashi in the Meiji Era

Source: National Diet Library

2) User-friendly Roads Can Be Traced Back to Early Times

Along with the establishment of the Seven Roads came

another system called “Ekiba, Tenma” (Post Horse System),

which eventually became the modern international word

“Ekiden” (a relay road race). In this Chinese-originated

system, an “Eki” (meaning station) was located at each

interval of 16km along a road and would provide necessary

services for the officials and people of high rank who

travelled that road on their journeys. Approximately 400

“Eki” were developed across the country. In the mid-8th

century, a number of fruit trees were systematically planted

along the Seven Roads, which eventually led to the tree lined

roads of today.

Later, in the 16th century, a road signage system called

“Ichirizuka” was established by referencing a similar practice

from ancient China. This system can be viewed as the Asian

version of the Roman milestone-system. After the Edo

Shogunate was established in 1603 C.E., the Ichirisuka

system was transformed when ample facilities

were created and the 5 Major Highway System,

radiating from Edo (the old name for Tokyo),

was formed. The Shogunate specified that the

five major highways should be about 11m wide

and secondary roads should be 5.5m wide. The

roads were to be filled with gravel and cobbles

to a depth of 3cm and topped with sand after

treading them down.

Sir Rutherford Alcock, the first British Minister to

visit Japan, wrote about his visit at the end of

the Shogunate era, saying, “Their highways, the

Tokaido, the imperial roads throughout the

kingdom, may challenge comparison with the

finest in Europe. Broad, level, carefully kept and

well macadamized, with magnificent avenues of

timber to give shade from the scorching heat of

the sun, it is difficult to exaggerate their merit."

3) Road Construction with a Consideration for People and Scenery

Japanese people frequently traveled, to such a degree that

foreigners were astounded by how far and how often they

traveled in comparison to themselves. The Japanese did not

hesitate to travel because there were such excellent road

facilities and services even back then.

In the middle of the Edo Era (1690 C.E.), Englebert Kaempfer,

a German doctor who came to Japan to work for a Dutch

trading house, wrote: “An unbelievable number of people

travel the highways of this country every day. The reason for

this is the high population of this country, but another

reason is that, unlike inhabitants of other nations, the

Japanese travel extremely often.”1

The Hakone Road was already paved by 1680 C.E. Sir Ernest

Satow, a British diplomat who came to Japan at the end of

the Edo Shogunate (mid-19th century), wrote in his book, “A

Diplomat in Japan,” about his astonishment at the pavement

there: “Next morning, we started at half-past six to ascend

the pass which climbs the range of mountains by an

excellent road paved with huge stones after the manner of

the Via Appia where it leaves Rome at the Forum, and lined

with huge pine trees and cryptomerias.”

Unlike the Via Appia, Japanese surface transport routes were

developed primarily for people and horses, because horsedrawn

carriages were not common prior to the Meiji Era

(~1868 C.E.) For this reason, roads were usually in good

condition since damage caused by traffic was not severe and

maintenance was relatively easy to complete. Road cleaning

and other regular maintenance was not performed by the

Shogunate or the government of feudal clans, but by

roadside residents on a voluntary basis. This implies that

there was a general understanding that roads were not the

exclusive property of the overlords, but considered to be

“public property”.

1 “Geschichte und Beschreibung von Japan”